How has it taken me so long to read Molly Gloss? I finally got to Outside the Gates in my TBR Stack, and it was amazing? I didn’t so much read this book as swallow it in a couple hours. It only took me that long because I kept making myself take breaks, both because I wanted the book to last longer (it’s pretty short) and also because I loved these characters so much, and I was so concerned for them I needed to avert my eyes a few times.

No spoilers, but I think you’ll be seeing more of Gloss’ work in this column.

I’ve been thinking about trauma. You may have seen a few weeks ago that The New Yorker published “The Case Against the Trauma Plot” by Parul Sehgal , which kicked up a flurry of conversation on Twitter…like literally everything does these days. The thing I liked about the article, and maybe agree with, is the idea that it’s become a fairly common move in fiction to build a story’s tension to a point when the main character’s trauma is revealed, often via A Harrowing Flashback, which could deepen the reader or viewer’s understanding of the character—but also risks turning fiction into simple algebra where we’re solving for The Tragic Event That Broke The Main Character.

But this has also been used for years—The Sparrow did it to horrific effect in 1996. So did, hell, Barbra Streisand’s film of The Prince of Tides, roughly a billion years ago. As I do with all intellectual puzzles, I put Sehgal’s points into conversation with the latest Spider-Man movie, which operates by processing some of Peter’s traumas while introducing new ones, in a fascinating undulating motion that mostly ducks around the typical MCU movie shape of building up to an emotionless CGI battle. The thoughts of trauma have stayed at the top of my brain because I’ve found myself turning questions of story shape over and over in my mind like Jareth’s crystals. Over my holiday break, I watched, well, a lot of things (I’m as quarantined as possible again) but among them were Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch, Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets, and Paul Schrader’s The Card Counter.

Again, not to worry, I’m not gonna spoil anything beyond saying that all three of these movies are good and you should watch them. The French Dispatch is four short stories woven into a wraparound narrative—since the titular magazine is based on The New Yorker, and since it’s Wes Anderson, the tone is arch and witty and, to my mind at least, delightful. (But it’s also worth noting that the Venn diagram of “my taste” and “things Wes Anderson likes to put in films” is a <futura>exquisitely centered goldenrod circle.</futura>) The structure means that the film is bumpy and digressive in the way flipping through a magazine is: one second you’re reading about the travails of a great painter, the next you’re in a restaurant review. It’s a fun way to shape a story so the emotional impact gradually coalesces around some loosely linked characters. For me, it didn’t all land, but the reason I’m talking about it here is that the fourth story, about a writer named Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright playing a fictionalized James Baldwin, which is the best collection of words in human history) deals with ongoing, unresolved, probably unresolvable trauma in one of the lightest and most delicate ways I’ve ever seen in film—precisely because it came at me gradually, quietly, and from a direction I didn’t immediately expect. And while there was a nested flashback at one point, it was not handled in a way that turned anyone into a math problem, it was a memory that grew, organically, from the character’s own thoughts and the situation he was in.

Mean Streets, if you’ve never seen it is a jittery frenetic rush through a few days in the life of a low-level, deeply religious mafiosa, Charlie, his erratic best friend, Johnny Boy, and his girlfriend Teresa. The “plot” is…actually, is there a plot? Charlie goes to bars, he attempts to collect money on behalf of his quietly terrifying uncle, he tries to clean up the messes his bff leaves in his wake, he goes to church, he tries to hide the relationship with his girlfriend, whose epilepsy makes her a pariah among the higher-level mafiosi who are the keys to moving up in the organization, he tries to tell people about the awesomeness of Francis of Assisi. But mostly, Charlie thinks really hard about how impossible his choices are; the drama of the film turns relentlessly on the clash between what Charlie thinks he wants, and what his small, violent world will actually allow him to have. There are no explanatory flashbacks or sepia-toned scenes from the characters’ respective childhoods—we’re trapped with them in real time, reacting on the fly.

[Yes, I know, I am getting back to the Gloss in a moment. Hang on.]

The Card Counter is entirely about trauma. It gives us a man who is living his entire life in the shadow of what was done to him, and what he did to others. We never know his background. We only know him, now, living each day as a form of penance—this is, after all, a Paul Schrader movie. We get one monologue that seems to bubble up against the character’s will., and I was hoping that would be it, but then Schrader also gives us two (extremely) Harrowing Flashbacks that show us some of The Tragic Event That Broke The Main Character. To my mind, falling into the structure of what Sehgal calls The Trauma Plot disrupts the film’s tone, and did veer a little too close into saying “this happened, and that’s why the main character will never know peace”, where I was much more invested in watching him flinch away from peace every time it was offered to him. (Having said all that the movie’s still great, and Oscar Isaac and Tiffany Haddish are both so good? Go watch it.)

Now why have I just dragged you through all of this Film Discourse to talk about a book? As I mentioned, this is the first Molly Gloss book I’ve ever read. I had no idea what I was getting into. So I was very excited when I realized that this month’s TBR Stack book fit in so well with my Ongoing Trauma Thoughts, and with a few of the movies I just watched. (My brain seems to work best when I can turn it into a red-stringed wall of connections and unexpected resonances.) Gloss’ book is about trauma, and healing from trauma, but it deals with it in such a delicate and subtle way that I’m honestly not sure I’ve read anything quite like it. What it reminded me of, immediately, was the Roebuck Wright section of The French Dispatch and The Card Counter, and, kind of, Mean Streets. Gimme a sec.

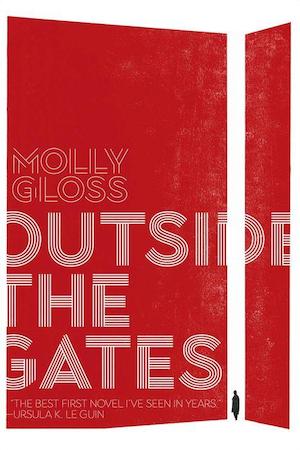

Buy the Book

Outside the Gates

To begin with, Outside the Gates is a very short book, a little under 100 pages, with a deceptively simple plot that never feels like a “plot” at all. It opens:

The boy thought his heart would stop from the thunder sound the Gates made as they closed behind him.

And then we’re off. The boy, Vren, has been cast out of the only world he’s ever known for reasons he understands but the reader does not. The Gates are a towering blank monolith that rise into the sky, uncaring and unyielding. In front of him lies an immense forest that, as far as he’s been taught, is a home to monsters and giants. The bones of other outcasts litter the base of the Gate.

We’re fully in the now—much as in the best parts of The Card Counter, actually. We only see Vren in the world outside the Gates, and we only get a few tiny direct glimpses of the society that lives behind them. I’m pretty sure that there is only one (1) Flashback in the entire book, and yes, it is Harrowing, but it’s also only a single sentence. And it isn’t what made Vren who he is—many elements made him who he is. Almost all of Gloss’ worldbuilding comes through in the way the boy behaves; like a sculptor using negative space, Gloss shows us Vren’s former society, its prejudices and beliefs, through the ways it shaped his personality. But she also makes it clear that Vren is far more than the pain that was inflicted on him.

Soon after he’s cast out, Vren is found by a man named Rusche. We initially see Rusche as Vren does: tall, strange, terrifying, with bristling brows and dark eyes. Vren’s been raised on tales of the monsters and giants of the Outside, and he’s sure Rusche will mean his death. Instead, the man takes the boy deep into the forest, to a small, warm hut “like a weaver-bird’s nest.” Rusche was also forces outside the Gates as a boy.

This could go in a lot of different directions. Rusche could see Vren as free labor, he could see him as a bargaining chip, he could see him as a chance at fatherhood, he could see him as a punching bag. He could see much darker things than I care to think about. But no, Gloss isn’t telling that kind of story. Rusche brings him home, shares his food. He doesn’t talk to him much because a lifetime of living alone has made him quiet. Here’s how we learn who Rusche is, and why he and Vren were cast out:

Sometimes, though, in that first autumn Rusche and the boy were together, rain fell hard right through the arms of the trees. Smetimes a wind flapped the clouds like sheets of cloth. Then Rusche—with a look in his face that was both cross and ashamed—would set a warm little whirlwind by the doorhole to keep the cold from blowing in.

And later, when Rusche realizes that Vren only pretends to eat the meat he brings to the table:

The man, through those first days together, only watched the boy silently from under his fierce red brows. Then finally, straightforward, he said. “You speak the languages of beasts, is it?”

The boy ducked his head. No one inside the Gates had given a name to his Shadow, as the man did now.

Thus we learn that the characters’ hinted supernatural powers are called Shadows, that they’re hated by the society within the gates, and that Vren’s ability is an ability to communicate with animals, which makes him a) very empathetic and b) vegetarian. And then we learn who Rusche truly is, because he throws all of his meat away. He doesn’t eat it in secret, or just eat what he has left, even though those are the more sensible options when facing a long, cold winter. He never pressures Vren to eat it in even the slightest way. He immediately, without hesitation, does what he needs to so that Vren will feel welcomed and safe.

In this moment we also get a sense of how repressive life within the gates must have been for Rusche, and we get a very clear picture of the strength of character that allowed him to survive outside.

The plot, when it comes for these characters, is built around their Shadows, and the way other people might want to exploit those Shadows. The important thing to me is that Gloss is careful at all times to allow the action to grow from who Vren and Rusche are, the core of them that exists beneath their talents and what society thinks of them—and she also keeps in constant touch with the fact that everyone outside the Gates lives with a bone-deep trauma that can’t simply be wished away. At each turn, Gloss avoids taking the easy route. No one here suddenly comes to terms with what’s been done to them and embraces their powers. As we meet more of the people who live Outside, we see that a very different book could exist, something more like an X-Men story, or a story of war and retribution. Instead Gloss gives space and warmth to characters who live lives curled around a shame they can’t look at directly. And then, very gradually, as the plot pushes the characters toward confronting that shame, Gloss allows her book to take a different type of shape. Rather than bloody battles or screaming confrontation, the book comes down to a few softly spoken words, and Gloss give her characters space to heal.

Leah Schnelbach knows that as soon as this TBR Stack is defeated, another shall rise in its place! Come discuss your trauma in the nefarious plot that is Twitter!